Credit control: carbon offsetting and making the voluntary carbon market more effective

David Burrows delves into the controversy around carbon offsetting, and examines the moves to make the voluntary carbon market more effective and reliable

At its heart, carbon offsetting is incredibly simple. The idea is to compensate for greenhouse gas emissions that cannot currently be reduced by paying for a certified unit of emission reduction or removal – anything from planting trees (nature-based solutions) to providing efficient cook stoves (technology-based offsetting). Individuals, businesses and even countries can offset their emissions.

Supporters see it as a critical tool in tackling climate change both now and into the future, provided it is done with integrity and that the project wouldn’t have happened without the additional funding. Reaching net-zero could be impossible without it, they say. Critics see it as a deceptively simple, corner-cutting alternative to carbon reduction, with Greenpeace calling it “the most popular and sophisticated form of greenwash around”.

Is there a role for offsetting in achieving net-zero? And if so, what does this look like?

A lack of nuance

The answer to the first question is ‘yes, but’ – and there are a lot of buts. These include the extent of offsetting (whether emissions have been reduced as much as possible), the type of offset, the credibility of the scheme or project, and the credibility of the claims being made.

Indeed, the nuance in this debate is being lost (or ignored) in the media narrative around it. There is talk of a ‘wild west’ market that allows polluters to keep on polluting. Fossil fuels companies, in particular, have come under fire for their shady use of offsetting, but fingers are already pointing at others who claim carbon neutrality, as well as schemes that allow them to do so.

“Offsets can make a difference, and they do make a difference,” explained Anne-Marie Warris, director of consultancy Ecoreflect and vice chair at Verra, a non-profit that runs the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) programme, during an IEMA webinar on the topic last year. However, she added, there are bad stories as well as good.

Offsetting has been a hot potato since the 1990s, when carbon management plans came to the fore. Roberta Barbieri, PepsiCo’s vice president of global water and environmental stewardship, summed up the issues in a podcast for Future Food when she said: “The concerns in the past are that offsets are a ‘get out of jail free’ card for companies – I’ll go plant some trees somewhere in the world and I’ll continue to emit greenhouse gas emissions guilt-free.”

Growing demand

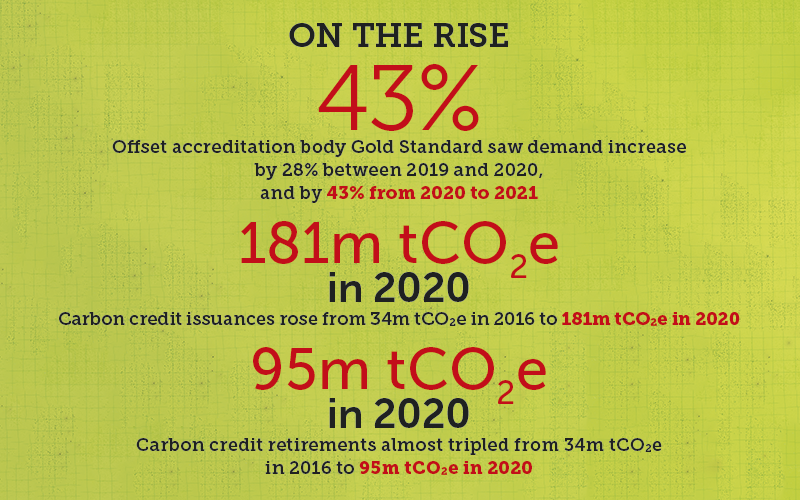

Demand for offsets surged in 2020 and 2021; Gold Standard, one of the leading project accreditation bodies for offsets, says demand for its services increased 28% between 2019 and 2020, and 43% from 2020 to 2021. Its senior director of communications Sarah Leugers says the climate marches played a part in driving this – which is ironic, given that Greta Thunberg, the campaigner synonymous with strikes and climate activism, is no fan of offsetting.

“There is certainly pretty hyperactive demand for businesses wanting to get forward on carbon credits”

Tom Popple is senior manager of climate change and sustainability at Natural Capital Partners, which works with the likes of Sky and PwC on carbon reductions and offsetting; he says there has been a “doubling or tripling” of demand for carbon credits. “There is certainly pretty hyperactive demand for businesses wanting to get forward on this both for carbon neutrality and net-zero,” he explains. The other push is coming from financial institutions, he adds.

One of the big stories to emerge from COP26 last year was the agreement on rules for a new global carbon market. Known as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, the framework offers a centralised system that is open to the public and private sectors and a separate one that will allow countries to trade credits. The agreement wasn’t without controversy – principally, the fact that millions of old credits can flood the new system – but will certainly grease the wheels of the carbon offsetting market.

Future forecasts

Data pulled together by the Climate Policy Initiative shows how the voluntary carbon market (VCM) was fairly flat until 2016, but then started to expand rapidly. The number of issuances – representing the supply side, when carbon credits are created or issued to a project, based on their independently verified emission reductions or removals – jumped from 34m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in 2016 to 181m tCO2e in 2020. Retirements – the demand side, when companies (or individuals) purchase carbon credits and use them for offsetting or other climate action claims – almost tripled in the same period, from 34m tCO2e to 95m tCO2e.

Future growth forecasts are even more striking. Using data on demand for carbon credits, projections by experts and the volume of negative emissions needed to reduce emissions in line with 1.5°C of global warming, McKinsey experts estimated that annual global demand for carbon credits could reach two gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2030, and as much as 13GtCO2e by 2050. Forecasting the value is trickier: the VCM could be worth anything between US$5bn and US$50bn by 2030.

That’s a lot of carbon and a lot of cash, so it will pay to get this right. Fossil fuel companies’ use of offsetting has cast a shadow over the market – “that keeps me awake at night,” says Leugers – but there is hope that more accountability will serve the sector well. The ‘burden of proof’ is higher now, the University of Oxford’s Thomas Hale suggested during the IEMA webinar. (Hale was involved in the creation of the ‘Oxford offsetting principles’ – a set of guidelines to help ensure offsetting actually contributes to achieving a net-zero society.)

Responding to criticism

Those involved in offsetting say companies are asking more questions. Before 2021, according to Popple, only one in five organisations probed for the detailed documentation that responsible, accredited providers should be able to produce; that figure is now much higher. The chain of custody is overseen by Icroa, the body that represents carbon reduction and offset providers; it has been fighting fires in recent months as criticism of the VCM surges.

Icroa isn’t alone: Verra has also recently had to react to criticism of schemes registered in its VCS programme, including one involving the fast-food chain Leon. More corporates making claims will mean more headlines, so businesses should tread carefully. A credible science-based target is now a prerequisite for being able to offset – and it should be remembered that the fossil fuel giants don’t have that in place.

“You need to innovate, you need to create a safe space for these new technologies to come through”

Reduction also trumps offsetting every time, but are providers hammering this home? Offsetting should be for unavoidable or residual emissions, which will be higher in some sectors, such as aviation, than others. Equally, offsetting is an attractive option for the here and now, allowing companies to show they are taking action. This leaves offsets vacillating between being a quick fix and a last resort, suggested the University of Manchester’s Robert Watt in his 2021 paper for Environmental Politics, ‘The fantasy of carbon offsetting’.

Addressing the issues

The reality is that the VCM is confusing and littered with traps. The Climate Policy Initiative has likened it to ice cream, with myriad flavours made using a variety of choice ingredients. Onto these you can sprinkle extras to enhance the offsets’ quality and appeal (one area to watch is the additional social benefits in some carbon offsetting schemes). “To make offsets as widely available as ice cream we need a liquid market with variety, multiple purveyors, industry standards, buyer choice, and consequences for bad quality and excess use,” wrote Climate Policy Initiative senior adviser Vikram Widge.

Supply could match demand, with credits coming from avoided nature loss (including deforestation), nature-based sequestration (such as reforestation), avoidance or reduction of emissions, and technology-based removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. McKinsey noted, however, that there are issues that could see supply shrink from a potential 8–12GtCO2e per year to 1–5GtCO2e.

One of these issues is the time lag between the initial investment and the eventual sale of the credits. This was picked up in an analysis completed by the Environment Agency earlier this year (Achieving net-zero – a review of the evidence behind carbon offsetting), which noted that two critical factors are how quickly the approaches produce greenhouse gas emission reductions or removals, and the length of time the climate benefits will be maintained for. For many of the 17 assessed approaches to reaching an impactful scale by 2030, implementation must begin “very soon”.

A credible system

This is a climate crisis, and emissions must be halved by the end of this decade. Can the standards that underpin the VCM keep up with this urgency without jeopardising offsetting’s reputation?

Much is expected of the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, an initiative spearheaded by ex-Bank of England governor Mark Carney that is working to scale an effective and efficient voluntary carbon credit market to help meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

A governance body has been announced, and now the work starts on creating a global benchmark to reassure buyers and critics that carbon credits are what they say they are. The Voluntary Carbon Markets Initiative, meanwhile, also promises to ease credibility concerns, focusing initially on how businesses can make climate claims around terms such as ‘net zero’ and ‘carbon neutral’.

Everyone was waiting to see how Article 6 panned out, says Popple, but established standards bodies such as Gold Standard and VCS are now considering how to incorporate more effective, credible solutions. “For supply to meet demand, you need new solutions,” he says. “You need to innovate, you need to create space for new technologies to come through, but not at the risk or detriment of the quality of offsetting.”

VCMs might not have worked perfectly to date, but the urgency of the climate crisis and heightened scrutiny of solutions could be just what’s needed to build a credible global system.

David Burrows is a freelance writer and researcher.

Image Credit | Alex Williamson | IKON